Workers' Comp Strategies

Cutting Down Agriculture Risk

Fatalities and injuries among forestry and agricultural workers have dropped significantly in recent years, but those occupations still rank among the nation’s most lethal. Unfortunately, the safety improvements contributing to that decrease don’t necessarily translate to lower workers’ compensation rates or fewer claims, according to experts.

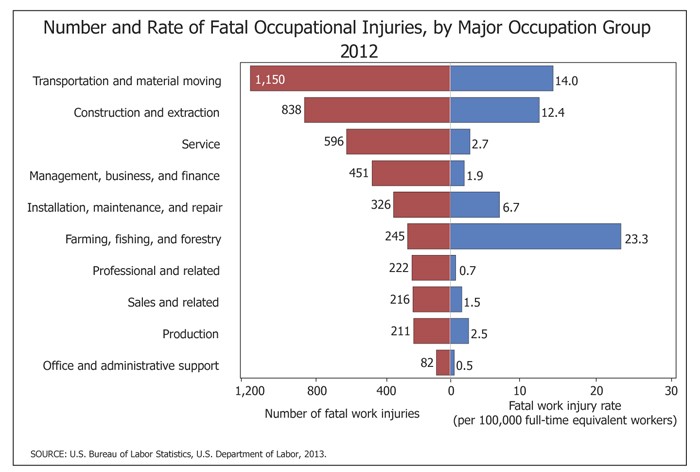

The Bureau of Labor Statistics rates logging as the country’s most dangerous job, with 128 fatalities per 100,000 full-time workers in 2012. Agriculture ranked ninth, with 21 fatalities, 9 percent lower than in 2011. The fatality rate for all U.S. workers was 3 per 100,000 full-time workers in 2012.

Insurance and academic experts attribute the improvements to safety technology and a vigilant focus on safety. However, “employee-oriented” workers’ compensation laws in some states, combined with rising medical costs, pressure carriers to raise rates, said Don Winn, managing director, Agriculture and Food Practice Group at Arthur J. Gallagher. “Carriers still tend to operate at underwriting losses,” he said. Medical costs account for around 70 percent of workers’ compensation expenses.

Well-run producers with favorable loss ratios can minimize those increases, Winn said. A determination of “well-run” includes safety protocols and implementation, buy-in from workers, and infrastructure to support a multi-lingual workforce. “Then they have positive results.”

Workers’ compensation claims and premiums cost the agriculture industry at least $4 billion per year in direct and indirect costs, said Stephen Reynolds, director of the High Plains Intermountain Center for Agricultural Health & Safety in Colorado, one of 10 regional centers funded by the National Institute for Occupational Science & Health (NIOSH) to research and recommend interventions to reduce agricultural and forestry injuries and illnesses.

Workers’ compensation claims and premiums cost the agriculture industry at least $4 billion per year in direct and indirect costs, said Stephen Reynolds, director of the High Plains Intermountain Center for Agricultural Health & Safety in Colorado, one of 10 regional centers funded by the National Institute for Occupational Science & Health (NIOSH) to research and recommend interventions to reduce agricultural and forestry injuries and illnesses.

Producers eat most of that cost in premiums, Reynolds said, but insurance carriers, taxpayers, and the food-buying public also pay. Injured workers and their families pay a huge cost in suffering and lost earnings.

Safety in the Woods

Agriculture and forestry environments include row crops to stockyards, and mountainous forests to sawmills. Each has its own risks. The most expensive claims for loggers, said John Lemire, director of loss control at Forestry Mutual, a North Carolina insurance company, are the million-dollar loss-of-limb cases both state and federal OSHA safety protocols seek urgently to avoid. Fully mechanized environments are the safest, where workers stay as much as possible inside the air-conditioned cabs of loaders, cutters, and skidders.

Thanks to member companies’ strict adherence to safety protocols and a financial self-interest in controlling exposure, Lemire said, Forestry Mutual’s claims dropped from 642 in 2004 for all their lines of business (trucking, logging, pallet mills and sawmills) to 210 in 2013.

Premiums for workers in a fully mechanized environment are fairly inexpensive, Lemire said, ranging from $8-$20 per person. That rate can soar to $50 per person, depending on the state, for workers using chainsaws on the ground.

Cutting trees from the safety of an enclosed, air-conditioned cab is more possible in the flat terrains of the Southeast, such as North Carolina and Georgia, than in the hardwood-rich mountains of the Northwest, where loggers are obliged to use chain saws and other dangerous equipment on steep and uneven terrain.

Even among those natural dangers, said John Hansen, senior safety management consultant at the Montana Logging Association, his organization has avoided fatalities for a number of years by adhering to state and federal regulations and using proper protective equipment for eyes, ears and legs. Loggers keep a close watch on overhead hazards — especially “widow makers,” branches caught on the top of trees that can crush workers below at any moment — and maintain a proper distance from falling trees.

According to Hansen, heat exposure, and slips, trips and falls account for many claims, as do bee stings. Highway accidents involving logging trucks account for many of the fatalities attributed to the industry.

The most frequent claims in agricultural settings result from slips, trips and falls; muscular and skeletal injuries from bending, lifting and stooping; skin diseases; and respiratory diseases caused by dust, bacteria and ammonia, such as those that afflict livestock and poultry farmers in enclosed facilities, Reynolds said.

Heavy equipment injuries, especially tractor rollovers, are a pervasive risk for agricultural workers, who are seven to eight times more likely to be killed on the job as the general working public. Those who work with livestock are at the greatest risk of injury and fatality, Reynolds said.

Controlling workers’ compensation costs for all of them starts with a demonstrated commitment by leadership to safety, said David Douphrate, assistant professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health. The second step is an accurate risk exposure assessment strategy and the third is safety training.

“Training makes a big difference,” Douphrate said. The perfunctory programs of the past — a 20-minute training video and a manual gathering dust on the shelf — aren’t nearly adequate for an increasingly immigrant workforce with low literacy and unpredictable language skills. “We need to stop training workers and start educating them, so they know why we’re telling them to do their jobs in a certain way.”

“We need to stop training workers and start educating them, so they know why we’re telling them to do their jobs in a certain way.”

—David Douphrate, assistant professor, University of Texas School of Public Health

Successful training programs universally include incentives, rewards and reprimands, said Gallagher’s Winn, and should be included in performance assessments. “You call out the guy who jumps off the equipment to save time and reward the one who uses the ladder.”

Refining the Message

Changing the safety culture demands figuring out what is important to farmers, said Julie Sorensen, a Ph.D. in epidemiology and deputy director of the Northeast Center for Agricultural and Occupational Health.

“Risk management is easy and cost-effective for farmers,” she said. “They know what they should and should not be doing, but they are not a risk-averse population.”

While promoting Rollover Protective Structures (ROPS), a highly successful shared-cost NIOSH tractor safety intervention program to prevent tractor rollovers, her organization learned that farmers fear permanent disability more than death, and they’re concerned about keeping their workers, wives and grown children safe while operating tractors.

Armed with that information, the Northeast Center created a marketing strategy that shows a farmer in a wheelchair and emphasizes safety to dependents. “We couldn’t look at the issue from our perspective,” she said. “We had to look from theirs.”

While producers can control their safety practices, they can’t control the legislative environment where they operate. California Senate Bill 863, which took effect in January, makes broad changes to that state’s workers’ compensation system, including increased benefits to injured workers.

As in other industries, employers, insurers and most often workers themselves aim for a prompt return to work after an illness or injury, even if they can’t return to their original jobs.

“There’s always something a recovering worker can do around a farm,” Douphrate said, but logging operations could offer fewer alternate duties.

Agriculture and logging are targets for insurance fraud because they employ many low-wage seasonal earners with low literacy and few employment options — itself motivation to seek alternate income sources.

To smoke out malingerers and fraudulent claims as well as to provide appropriate medical care to legitimately injured workers, the Georgia-based third party administrator Broadspire uses a proprietary software system that guides adjusters through telephone interviews, conducted in the claimant’s own language.

The software poses a set of questions to capture the psychosocial aspects of a claim that could indicate fraud or exaggeration: Do you smoke? Are you diabetic? Do you hate your boss? How bad is your pain?

Responses, said Donnie Gray, senior vice president of Casualty Claim Operations, trigger related questions. The software flags inconsistencies between the answers and notes by medical professionals and case managers.

The best strategy for controlling workers’ compensation costs, said Bob Bollinger, a North Carolina attorney who represents injured workers, is to neutralize hazards on the front end. Once workers are hurt, he said, treat them well. Call them, take them to the doctor, don’t deny legitimate claims.

“My clients come to me because they’re angry and feel their employer is treating them unfairly. Keep lawyers out of it,” he said.