2015 Most Dangerous Emerging Risks

Aquifer: Nothing in the Bank

SCENARIO: Jon Gullo eyed the monitor as the nanobots burrowed underground, searching for moisture.

He and his lawyers had managed to convince regulators to let him explore the apparently empty aquifer under his 115 acres of almond trees in California’s Central Valley.

The nanobots were a last-ditch effort to find adequate water supplies in the face of a drought that was browning what had been the country’s richest agricultural zone.

Regulators were helping. Every other week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture collected data from satellites as they passed over the Western states. Like the nanobots, the satellites were searching, in vain mostly, for signs of water in the depleted aquifers, many of which had been pumped dry due to public and private sector mismanagement.

Now the chickens were coming home to roost. With the aquifers depleted, an economic sea-change was in the offing.

In the drought’s early years, businesses and governments invested billions in water recycling, desalination, and freshwater capture, storage and transport. They also drilled deeper and deeper into the aquifers, until stronger regulation of groundwater usage took effect. But the efforts couldn’t stop the aquifers, long a buffer against drought, from running dry.

Now the chickens were coming home to roost. With the aquifers depleted, an economic sea-change was in the offing.

Agriculture, one of the state’s biggest water users, was bearing the brunt of the shortage, and consumers paid for it at grocery stores and in restaurants. Although other areas of the world were ramping up production, fields were not producing fast enough to keep up, plus several batches of imported fruits and vegetables were found to contain traces of banned pesticides.

As the shortage continued, California’s politically powerful cities refused to take deeper cuts in their share of the remaining water supplies. And it was too costly in rural areas to pipe in water from desalination plants, or engage in the same aggressive recycling and conservation efforts used by larger metro centers.

Most of Gullo’s neighbors were already gone. His orchards were surrounded by fields of sand and dust, and abandoned food processing plants.

Undaunted, he was hoping to squeeze what he could from the depleted aquifers under his property.

The potential payoff was worth it, reasoned Gullo. Almonds were fetching astronomical prices thanks to production declines in the Central Valley, which had been the world’s leading grower.

Although he hesitated to admit it, he was frightened to try to sell his property. Few wanted to move to an area where jobs were disappearing and water was so scarce and expensive.

The dearth of homebuyers spurred by the water shortage resulted in a mini-foreclosure crisis up and down the Central Valley.

At least his county had oil and mining to fall back on, though automation and climate-change regulation had put dents in the workforce.

All newcomers could hope for were jobs in construction — fixing the damage to roads and bridges caused by the land subsidence that occurred after the aquifers ran dry.

But if there were no trucks ferrying crates of grapes, almonds and oranges, who needed roads?

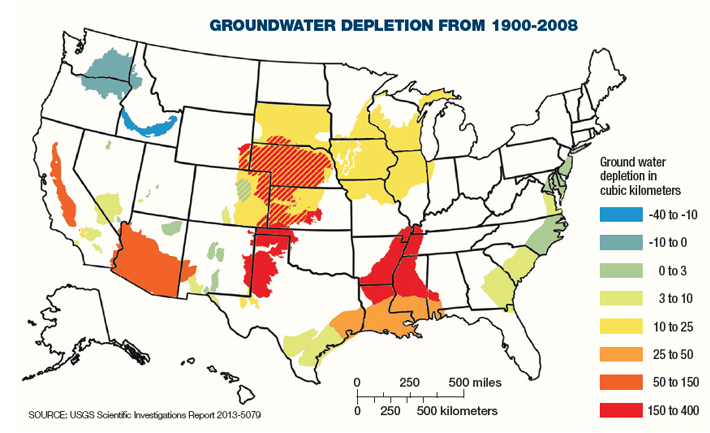

ANALYSIS: As California’s drought wears on, no needles register precisely the decline of aquifers in the Central Valley, one of the country’s leading agricultural regions.

But water levels are clearly dropping. In some areas, the land has subsided more than a foot.

Ideally, the return of normal rainfall patterns will replenish the aquifers, though a full refill could take decades. However, the odds of even longer droughts — and even more strain on underground aquifers — are rising, according to climate scientists.

They cite the impact of global climate change, as well as the geological record. Medieval-era droughts in the American Southwest lasted 30 years or more.

Aquifers served as a buffer for those populations, which nonetheless succumbed to malnutrition and conflict, said B. Lynn Ingram, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley. That buffer is shrinking today.

“It’s kind of like the water in the bank that we’re using up now,” said Ingram, author of “The West Without Water.”

It’s not just a U.S. problem. Aquifers around the world are emptying, according to research by James Famiglietti, a professor of earth system science at the University of California, Irvine. Sao Paulo in Brazil, for example, has been hit hard, with the city experiencing widespread water shortages.

While modern economies are more technologically advanced, an extended drought and continued aquifer depletion would be painful, especially for agriculture.

The U.S. could see higher food prices and disruption to supply chains, according to insurance and agricultural experts.

The U.S. food supply is becoming more resilient, thanks to interest in local farms, said Dawn Thilmany, a professor of agricultural economics at Colorado State University.

But local farmers won’t be able to make up everything, and water scarcity may not be limited to California.

One alternative is crops genetically modified to withstand drought, experts said. More efficient water use is another. But as the globe warms, production may ultimately shift to northern states.

Imports from other countries also might make up the difference, but they bring new risks, especially if growers overseas are using pesticides or fungicides banned in the U.S., said Rodney Taylor, a managing director in the environmental services group for Aon Risk Solutions.

To guard against liability risks, food distributors and processors should scrutinize any new producers, said Tim McAuliffe, president of specialty casualty and programs for Ironshore. If crops shrink and prices rise, producers may be less rigorous about quality control.

VIDEO: California Gov. Jerry Brown announces the state’s first-ever mandatory water restriction rules.

New sources of surface water also pose a risk of contamination, as does water from deep inside an aquifer, he said. “I would call those a little more remote. But if the drought does continue at severe levels, it’s something that we would watch a lot closer.”

In California, urban areas could recycle wastewater and desalinate ocean water, said David Sedlak, a professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at U.C., Berkeley. While costly, those efforts will keep the taps flowing.

“It’s just hard for me to imagine a situation where the cities run out of water,” said Sedlak.

Still, the shortage of water could have ripple effects. Electricity production, for example, may be stretched if dams are less productive and higher temperatures translate into greater demand.

“You could end up having situations where you have brownouts because there is so much strain,” said Kirsten Orwig, an atmospheric perils specialist for the reinsurer Swiss Re.

Risk managers will have to consider access to water when assessing supply chains and new operations, insurance executives said.

And if conditions stay dry, wildfires will worsen.

Interstate conflicts over water will flare, too, said David Bookbinder, a partner at Element VI Consulting, which focuses on climate change policy.

Aquifers and watersheds don’t follow state boundaries, he noted. The Supreme Court usually winds up arbitrating disputes over water.

“It’s problematic that our political structure is not set up to deal with this,” Bookbinder said. “That, I think, is going to be the biggest problem.”

Complete coverage of 2015’s Most Dangerous Emerging Risks:

Corporate Privacy: Nowhere to Hide. Rapid advances in technology are ushering in an era of hyper-transparency.

Corporate Privacy: Nowhere to Hide. Rapid advances in technology are ushering in an era of hyper-transparency.

Implantable Devices: Medical Devices Open to Cyber Threats. The threat of hacking implantable defibrillators and other devices is growing.

Implantable Devices: Medical Devices Open to Cyber Threats. The threat of hacking implantable defibrillators and other devices is growing.

Athletic Head Injuries: An Increasing Liability. Liability for brain injury and disease isn’t limited to professional sports organizations.

Athletic Head Injuries: An Increasing Liability. Liability for brain injury and disease isn’t limited to professional sports organizations.

Vaping: Smoking Gun. As e-cigarette usage rises, danger lies in the lack of regulations and unknown long-term health effects.

Vaping: Smoking Gun. As e-cigarette usage rises, danger lies in the lack of regulations and unknown long-term health effects.

Aquifer: Nothing in the Bank. Once we deplete our aquifers, there is nothing helping us get through extended droughts.

Most Dangerous Emerging Risks: A Look Back. Each year since 2011, we identified and reported on the Most Dangerous Emerging Risks. Here’s how we did on some of them.