Workers' Comp

Putting a Cap on Physician Dispensing

“If someone told you, as a physician, you could earn an extra $75,000 to $200,000 per year without having to see any additional patients, work more hours or increase your overhead, wouldn’t you like to know how?”

So begins an ad from MedX Sales Ltd., designed to create interest in MedX’s prescription repackaging and workers’ comp medical dispensing program. The four-minute ad goes on to state that some physicians handling workers’ compensation who sell MedX’s prepackaged generic and name brand medications to patients directly have “literally doubled their income” as a result.

Sound seductive? It is.

And yet, these sorts of promises from prescription drug repackagers are like most things that sound too good to be true, according to industry experts representing workers’ compensation payers including insurers, self-insured employers, TPAs and state workers’ compensation funds.

They fail to explain that when physicians sell prescription drugs to comp claimants directly, employers, insurers and other payers can expect to receive bills that are 100 percent to 700 percent more than invoices for identical medications dispensed by retail pharmacies like Walgreens and CVS. So said Joe Paduda, president of CompPharma, LLC, a consortium of the nation’s leading pharmacy benefit managers that are active in workers’ compensation, headquartered in Madison, Conn.

In total, Paduda estimated that physician dispensing adds a billion dollars to employers’ workers’ comp premiums annually.

The issue is most pronounced in workers’ compensation, since “workers’ comp is basically dealing with pain, inflammation and so on,” with physicians often dispensing simple and inexpensive drugs like ibuprofen — possibly dispensing them at a factor of three to 10 times the price of over the counter, said Jacob Lazarovic, M.D., senior vice president and chief medical officer with Broadspire, a TPA to employers and insurers, based in Sunrise, Fla.

“The dispensing physicians can have a very small menu of 10 to 15 drugs including generally less potent opioids including the generic versions of Vicodin and Percocet, and that’s all they need to dispense drugs to all their compensation patients so it’s a very simple process,” said Lazarovic.

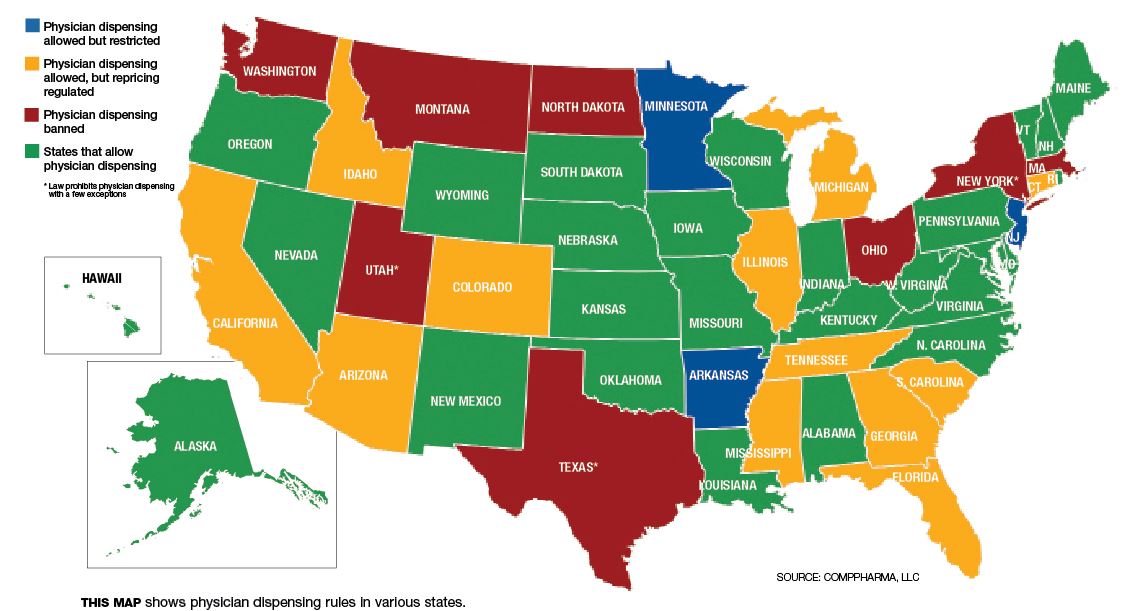

To address these kinds of problems — as well as safety issues that have emerged when doctors take on the role of pharmacists without the same kinds of information about patient histories and drug interactions — many states have adopted rules restricting or banning physician-dispensed medications.

California, for instance, first amended its fee schedule regarding physician-dispensed drugs in March 2007. The guidelines in question required that the relevant fee schedule for physician-dispensed drugs be based on the original manufacturer National Drug Code (NDC) for the drug — the very same rule that applies to pharmacies. Such rules override a loophole in national regulations set by the Federal Drug Administration, wherein a repackager is a manufacturer able to set its own NDC code and can price prescription drugs at the average wholesale price of its choosing.

The results have been staggering. Alex Swedlow, president of the California Workers’ Compensation Institute (CWCI), observed in a February 2013 report that from 2002 though 2006 — prior to the reform — physician-dispensed repackaged drugs climbed to nearly 60 percent of California’s total workers’ compensation prescription drug payments.

Today, the figure is less than 2 percent, Swedlow said. In the past, “it was not unusual to see a 1,000 percent difference for the same prescription” sold directly by doctors versus pharmacies, but today that extreme profit incentive no longer exists, he emphasized.

So far, states that have followed California’s lead in equalizing reimbursement rates include Arizona (October 2009), Georgia (April 2011), South Carolina (December 2011) and Tennessee (August 2012).

In California, meanwhile, the Swedlow study found that during the pre-reform period, when physician-repackaged drugs represented more than half of all drugs prescribed in California workers’ compensation, paid medical benefits on physician-dispensed repackaged drugs averaged $5,524, or 16.4 percent more than the $4,747 average for claims without them. Even after the March 2007 reforms, paid medical benefits on claims involving physician-repackaged drugs averaged $7,297 — 37.3 percent more than the $5,316 average for claims without these drugs.

In addition, the study found that comp claims with physician-dispensed repackaged drugs had a higher average number of paid temporary disability (TD) days. “Combining the pre- and post-reform results shows that from 2002 through 2011, claims with repackaged drugs averaged 44.1 paid TD days; 8.9 percent more than the average of 40.5 days for claims without repackaged drugs.

This finding challenges a critical statement often heard from repackagers — that the convenience of obtaining prescriptions from doctors should reduce the cost of medical care and facilitate quicker return to work.

“We found the opposite,” said Swedlow.

Reforms Reduce Opioid Use

Another state that has set its own standard as far as prescription drug repackaging is concerned is Florida. The state’s ban on physician dispensing of certain “stronger opioids” went into effect July 1, 2011. A study from the Workers’ Compensation Research Institute (WCRI) released this past July found that the Florida law reduced the overall use of opioids prescribed for injured workers in the state.

Apparently, the average Florida physician-dispenser continued to dispense pain medications after the ban, but increased the use of less addictive pain medications like ibuprofen and tramadol.

“The physician-dispensers could have continued to prescribe the stronger opioids (e.g., hydrocodone-acetaminophen), but would have been required to send the patients to pharmacies,” WCRI stated when it released the findings. The study reported no material change in the percentage of patients who received stronger opioids from pharmacies.

Paduda observed that before the Florida changes, 5.7 percent of the prescriptions dispensed by doctors were opioids that fell under the ban. “After? 0.6 percent, and almost all of those were dispensed by docs outside of Florida for Florida claimants. Moreover, there was no appreciable increase in the volume of opioids dispensed by retail pharmacies, implying that the physicians who were prescribing and dispensing strong opioids stopped doing so when they could no longer dispense the medications from their own offices.”

A serious concern with drug repackaging and direct sales by physicians is the risk it poses for patient safety and potential drug interactions.

“Many times prescribing physicians will ask patients, ‘Are you taking other medications?’ and patients don’t know exactly what drugs they are taking,” said Robert Bonner, M.D., vice president of medical practices and medical director with The Hartford.

“The pharmacist has an automated system to check for potential drug interactions,” Bonner observed, whereas individual doctors do not.

One problem, he said, concerns patients who receive “second or third line drugs” that were once popularly prescribed but are no longer the drug of choice for a particular condition.

For example, a muscle relaxer known as Carisoprodol, marketed under the name Soma, and first developed in the 1950s, “is not used much anymore but is fairly common with physician dispensing,” said Bonner.

Often the process of drug repackaging and physician sales leads to patients receiving questionable medications, one source suggested. A 2006 study by CWCI found that acid blocker Ranitidine (the generic version of Zantac) also had one of the highest mark-ups when dispensed by physicians at the time, at $2.97 per pill when pharmacies were paid 18 cents — a 1,700 percent differential. Ranitidine was the most physician-dispensed drug at the time of the report.

“Usually, physicians would prescribe this drug for patients if they had trouble tolerating ibuprofen or aspirin,” said Bonner. But some doctors were automatically dispensing Ranitidine, prompting questions of whether the drug was medically indicated or precipitated by a profit motive.

Fighting Back

Paduda of CompPharma pointed to a few remedies being used for the repackaged drug problem:

* A number of payers are directing injured workers to go to physicians who don’t dispense their own drugs. This has been happening in California, Florida and Connecticut.

* Where critics are questioning the medical necessity of a particular drug a physician is dispensing, utilization review regulations may be used to contest the use of the dispensed medication.

* In many states, insurers are declining to pay bills where doctors are dispensing medications, requiring physicians who wish to contest the practice to take their complaint to an administrative law judge.

Broadspire has begun a pilot program, contacting physicians in Georgia and Pennsylvania who are dispensing drugs and telling them why the practice is questionable, said Lazarovic. Aiding Broadspire with the effort is HealthCare Solutions, Broadspire’s PBM.

“The preliminary result after one quarter’s worth of data is that physician-dispensed drug costs have declined by 9 percent” among those doctors who were part of the pilot, Lazarovic said.