What’s a Gigafire? And How Could It Impact My Business?

Gigafire. The term itself is enough to keep the insurance industry awake at night.

A gigafire is defined as a wildfire that burns one million acres.

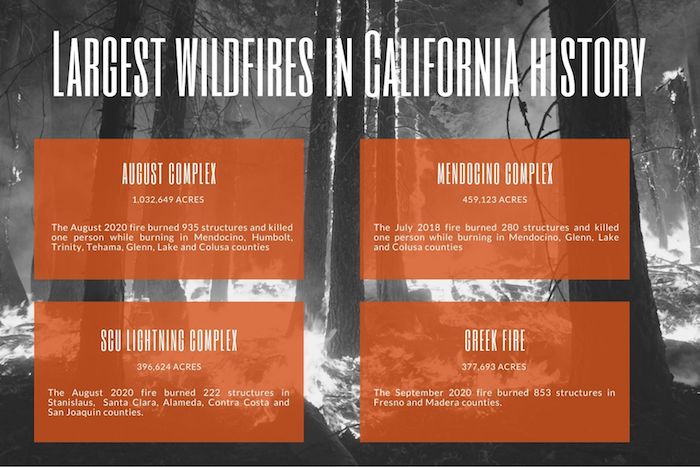

The recent August Complex fire reached that ominous designation. Ignited by a series of lightning strikes, it grew into a powerful force, burning in seven California counties. It’s the largest fire in California history according to Cal Fire, more than doubling the acreage burned in the Mendicino Complex fire in 2018 — the second ranked fire on the list.

The National Interagency Fire Center reports that there were three other gigafires in recent history:

- 2020: Two brush fires in Australia combined to burn 1.5 million acres.

- 2004: Taylor Complex in Alaska burning 1.3 million acres.

- 1998: The Yellowstone Fire in Montana and Idaho burned 1.58 million acres.

The origins of the term “gigafire” are unclear — but could date back to Wildfire Today and a seemingly innocuous Twitter conversation.

The magazine wrote in 2018: “When we coined the term ‘megafire’ for wildfires that exceed 100,000 acres, it was in the back of our mind that if a fire reached 1 million acres it would be called a ‘gigafire.’ ”

Fast forward to 2020 and a Wildfire Today reporter asked his Twitter followers what to name a fire that burned 1 million acres — and one respondent said: “gigafire of course.”

Wherever the term originated, it’s here — and likely here to stay.

“There is the anticipated expectation that this will not be the only one. We do have the risk, as a society, of seeing more of these massive fires,” said Tom Larsen, principal of insurance solutions at CoreLogic. “It’s not going to be something we see all the time, but there are pressures that lead us to say it could occur even if it’s very infrequent.

Take the August Complex fire, for example. It was ignited by 38 lightning strikes. That’s due to tropical storms and thunderstorms becoming more and more powerful as a result of climate change.

“They’re very rare, but you could have 50 to 100 lightning strikes simultaneously,” said Larsen.

It’s important to make the distinction that acreage burned does not directly correlate to insured losses. In fact, the August Complex fire ranks 17th on the list of the most destructive California wildfires, according to Cal Fire.

The top five show a wide range of acreage burned. The most destructive, the Camp Fire incident from 2018, destroyed more than 18,000 structures, killed 85 people, but burned approximately 10% of the acreage of the August Complex wildfire.

“There’s a disconnect. The size of the fire and the size of the insurance loss are not strongly correlated,” said Larsen.

Mark Sektnan, vice president of the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, added that “the two massive fires we had in terms of acreage both happened in relatively unpopulated areas. [If] one of these was to hit a highly populated area, the implications would be disastrous.”

Wildfire Season Is Getting Longer and More Unpredictable

When Sektnan began working in the field years ago, the seasonality of wildfires was predictable: He’d start the radio interview circuit in June and July, reminding people to prepare for the wildfires coming in October when autumn winds were heaviest. This year, major fires started in August and some burned into November and December.

“We say we don’t really have a season anymore, and I think the fire officials are starting to say that now, too,” said Sektnan. “Wildfires are something we need to prepare for year round.”

Fighting fires for months leaves firefighters with less time for suppression efforts like removing the burnable vegetation in vulnerable areas.

Dry leaves, branches and pine needles combine with dense forests to become the kindling that fuels wildfires. Controlled burns can help but there are environmental implications of putting toxins in the air — plus firefighters don’t have as much bandwidth for such efforts. The state even deploys prisoner inmate fire fighting forces, but many have been sidelined in 2020 because of COVID-19.

Still, Larsen said that suppression efforts are getting stronger long term.

“There is hope that we’re going to get better at fields management,” said Larsen. “The hope is that there will be better coordination and better forestry management in the future.”

Securing insurance coverage amidst growing wildfire risk comes with added complexity. In the commercial markets, businesses are turning to surplus lines.

“The price is going up because the average annual loss and the overall risk is higher,” said Larsen. “There are a number of areas in the state with concentration risk as well. We saw one small carrier go insolvent after the wildfires. So that’s making a lot of carriers want to back out or do a lot more underwriting.” &