Public Sector

Guaranteeing Performance

In September 2008, the state of Indiana was ordered to reimburse the consortium that operates the Indiana Toll Road $447,000 for tolls waived for travelers evacuated during a severe flood.

The trigger was a compensation clause in the 2006 leasing agreement between the state and the private group that provided the state with an upfront payment of $3.8 billion in exchange for the consortium’s right to operate the 157-mile toll road for 75 years.

Such clauses guarantee that governmental entities compensate private operators when there’s an event affecting the leased asset’s revenue.

That 2008 cost to the state government of Indiana is just one of the risks that may crop up as public-private partnerships — or P3s — are used more by cash-strapped governments as a means to shore up or operate aging U.S. infrastructure.

More recently, the consortium that paid Indiana for the right to run the highway encountered liquidity problems, leading to even more uncertainty over the highway’s future management.

The consortium’s timing was bad. It paid billions to take over the toll road right before the onset of the Great Recession.

P3s are fairly common in Europe and Canada, especially as a way to design, construct, and fund social infrastructure such as courthouses and hospitals.

But here in the United States, P3s are still in their infancy, and some surety carriers look at them skeptically.

“I have not seen a single project recently where the surety industry has not been able to provide a 100 percent performance and 100 percent payment bond.”

— Drew Brach, a Marsh managing director and U.S. surety practice leader

The arrangements permit governments to contract with private financiers and lending institutions to build, finance, operate and maintain major infrastructure development, with private entities covering the upfront costs in exchange for the ability to run the facilities and to collect tolls or other payments for long periods of time.

The “operating and maintaining” phase of an infrastructure project often ranges from 25 to 40 years.

Carrier Concerns

Carriers are particularly concerned that many states using P3s have yet to enact enabling legislation calling for the payment and performance guarantees that surety underwriters typically provide on infrastructure development.

Although a total of 34 states have laws enabling P3s, only 26 of those states require payment and performance bonds on P3 projects, said Mary Alice McNamara, second vice president and counsel with surety provider Travelers Bond & Financial Products.

Examples of some recent P3 projects that have surety bond requirements include California’s Presidio Parkway program, Ohio’s River Bridges East End Crossing program and the Indiana and Illinois Illiana toll-road project, McNamara said.

When surety bonds aren’t required to guarantee project completion and payment to subcontractors, suppliers, and laborers for work performed on P3 infrastructure projects, lenders may call for letters of credit (LOCs) instead, as performance security.

However LOCs “don’t offer any payment protection to subcontractors, suppliers and laborers who have worked on the job,” said McNamara, who also stressed that “LOC beneficiaries will be the ‘concessionaire’ ” or private investors providing the financing for the P3.

“A performance bond guarantees to the owner of the project that the project will be completed according to the underlying construction contract,” she said.

“A payment bond guarantees that subcontractors, suppliers, material, men, and laborers who have provided labor, services, or supplies to a project will be paid.”

Moreover, LOCs tend to be in an amount covering only a small portion of a project, often just 10 percent to 20 percent. Payment and performance bonds, on the other hand, “each provide up to the full amount of the construction contract,” McNamara said.

And yet P3s are a tempting concept at a time when national infrastructure needs and public sector budgetary challenges are so acute.

Deficient Roads and Bridges

Six years ago, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) warned that the country’s bridges would reach their average expected lifespan of 50 by 2015.

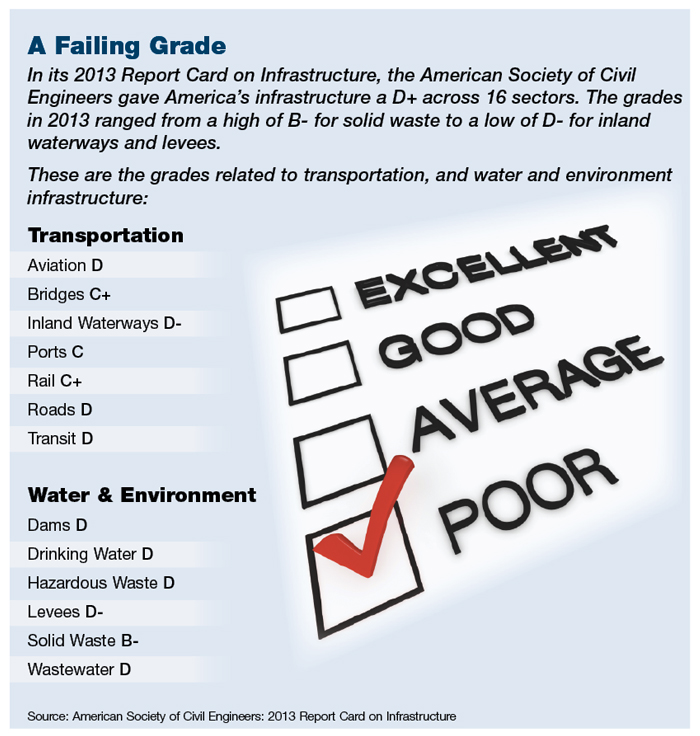

In 2013, the American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) “report card” grade for America’s infrastructure was a dismal D+.

“Deficient roads, bridges, and ports hurt our GDP, our ability to create jobs, our disposable income and our competitiveness with other nations,” ASCE President Randall Over said in April.

So little has been done to shore up the nation’s bridges and other infrastructure that ASCE estimated deficient and unreliable surface transportation will cost each American family $1,090 a year in disposable income by the year 2020.

At a time when there is serious pressure on public entities to stretch their infrastructure project capacity, many state and municipal officials are looking to P3s for assistance, said Dorothy Gjerdrum, senior managing director of Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.’s public sector practice.

However risk specialists and decision-makers need to know the potential pitfalls of these arrangements and consider the broad range of uncertainties, she said.

Risks and Responsibilities

Gjerdrum, who spent more than a decade as a risk manager for a pool of county governments in New Mexico, said that there are a myriad of risks and legal issues involved when implementing a P3, including the review of the contractual agreement and which parties will be responsible if there is a major loss.

“There needs to be a significant review as to who is in the best position to bear the consequences if something happens,” Gjerdrum said.

“Sometimes public entities will take on too much responsibility for the things that can go wrong,” she said. Alternatively, “they may be too trusting that the large private organizations with whom they have partnered with will bear responsibility.”

“In a P3 situation,” said Travelers’ McNamara, “risks that would have traditionally been kept or retained by the public entity project owner are being pushed entirely down to the concessionaire level.”

Design builders who once negotiated with public entities are now dealing with a private concessionaire entity instead, she said.

Beyond that, different coverage issues will arise once a building or renovation project moves from the “design-build” phase into the “maintain and operate” phase. These issues call for the involvement of multiple insurance experts and good risk management oversight, said Gjerdrum.

“One example is whether (and how) sovereign immunity will apply if a facility is owned by a public entity but operated by a private business,” she said.

Sovereign immunity in many circumstances means that the sovereign or government involved in a project is immune from lawsuits or other legal actions.

“What happens if the private business fails? What if revenue projections fall short? What if the environment changes and the service or facility is no longer viable?” Gjerdrum asked.

“P3 solutions can help public agencies solve a myriad of infrastructure problems, but managing the associated risks requires thorough review, long-term thinking and good oversight,” she said.

There are clear advantages to P3s too, of course.

Virginia pioneered the P3 concept more than 20 years ago with a prison that was privately designed and built, according to Governing the States and Localities magazine.

“The prison, which ended up costing $42 million to construct, had to be built to state specifications, but the private company had its own design ideas that arguably were more efficient and less expensive,” according to the magazine.

“The point they made was they could build it cheaper,” Michael Maul, associate director of the Virginia Department of Planning and Budget, said to the magazine.

“It was built more quickly and for less cost.”

Virginia officials estimated that using a P3 to build and operate the prison would generate savings of between 15 percent and 20 percent.

Industry Critics

But some in the insurance industry are weighing in with their own concerns. Among the critics is the industry group, the Surety and Fidelity Association of America (SFAA).

In its 2012-2013 SFAA Annual Report, the organization stated its position that P3s are “just another method of project delivery” and that “the construction portion of the project needs to be bonded under the Little Miller Act.”

The Little Miller Act — which is based on the federal Miller Act — requires state contractors to post performance bonds.

“By issuing a bond, the surety provides the public entity and the taxpayers and subcontractors with assurance from an independent third party, backed by the surety’s own funds, that the contractor is capable of performing the construction contract. The other primary benefit of the bond is that the surety responds if the contractor defaults,” the SFAA stated.

Insurers are working with P3s, however. Stephen Rea, general counsel for Liberty Mutual Surety in Boston, said that Liberty “has written bonds for P3 projects in states where enabling legislation requires public work to be bonded under Miller or Little Miller Act legislation.”

Drew Brach, a Marsh managing director and U.S. surety practice leader, said that he has done work with several P3s, adding that surety bonds were obtained for each and every one of the deals.

Strain on Capacity

Surety industry capacity may also become more of an issue as P3s gain momentum.

Given that P3 projects are often valued at $500 million and up, project size could be a strain on a smaller surety provider’s ability to underwrite projects, said Roland Richter, vice president, marketing and analytics for Liberty Mutual Surety.

“Only a handful of sureties have sufficient capacity to bond P3 projects,” he said.

“Thus, as some of these P3s move forward, smaller surety companies may find an erosion in their premium base as their customer base may not be large enough to bid P3 projects,” Richter said.

On the other hand, Rick Ciullo, chief operating officer at Chubb Surety, said that surety underwriting capacity has been on the rise since 2007.

“Contractors became better risks during the construction boom of 2002 to 2006, though they may have had trouble getting surety capacity because the surety industry was losing money during this construction boom.”

Ciullo said he has seen many more projects within the industry valued at over $500 million bound by surety insurers since 2008.

Marsh’s Brach has also seen surety industry capacity grow over time. Five years ago, Brach said, if you asked an underwriter to issue a $3 billion bond, the answer was generally “no,” said the brokerage executive.

But that’s changed, he said — even for larger projects.

“Some sureties say we’re going to analyze case by case what bonding is required [for a P3 program] and decide what the risk is.

“I have not seen a single project recently where the surety industry has not been able to provide a 100 percent performance and 100 percent payment bond,” said Brach.