Life Science

Countering Counterfeit Drugs

We have all received them – spam emails offering cheap Viagra or other such male enhancement drugs.

Chances are that they’re one of the millions of counterfeit drugs that flood the pharmaceutical market every year.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that at least half of all drugs sold today on illegal websites that conceal their physical address are counterfeit. While counterfeit drugs account for only 1 percent of all medicines sold globally, that still amounts to $200 billion, according to the International Institute of Research Against Counterfeit Medicines.

Law enforcement agencies across the world have seen a huge increase in the manufacture, trade and distribution of counterfeit, stolen and illicit medicines in the last 10 years, with the WHO estimating that worldwide sales have increased by about 90 percent since 2005.

“Counterfeit medicines affect all types of legitimate drugs and threaten the entire health system by creating mistrust.” — Cyntia Genolet, associate manager, regulatory and health policy, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations

“Counterfeit medicines affect all types of legitimate drugs and threaten the entire health system by creating mistrust,” said Cyntia Genolet, associate manager, regulatory and health policy at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA).

“They can be fake versions of patented, generic or over-the-counter medicines, and exist in all therapeutic areas.”

Counterfeit drugs not only put at risk the lives and health of millions of patients who believe that their prescription medicines are both safe and effective; they also cost the pharmaceutical industry billions of dollars in lost revenue every year and leave companies exposed to a host of reputational and liability risks.

Increasingly complex global supply chains, the rise of internet pharmacies and new advancements in technology have all made it far easier for criminals to produce and sell counterfeit drugs.

“We are seeing a geographical intensification of counterfeiting which is no longer focused on one or two parts of the world, but is now global, largely because of the internet,” said Geoffroy Bessaud, associate vice president of anti-counterfeit coordination at Sanofi.

Risk to Human Health

The main risks of taking counterfeit drugs are that they may contain the wrong ingredients, or they may contain too little, too much or no active pharmaceutical ingredient or API (which is what makes the drug effective) at all, according to Matthew Bassiur, deputy chief security officer at Pfizer.

That means patients are not receiving the therapeutic value they need and may suffer adverse effects of taking the wrong ingredients, ultimately putting their health, and lives, at stake.

“It really becomes a game of Russian roulette because you have no way of knowing what it is you’re ingesting,” Bassiur said.

In some cases, these drugs have been found to contain toxic substances such as leaded highway paint, floor polish, brick dust, antifreeze and even rat poison, often because they are being manufactured in unsafe and dirty conditions, he added.

“Counterfeit medicines are being produced in some of the most deplorable and unsanitary conditions imaginable,” he said. “So it’s no surprise that you find these kinds of contaminants in these bogus drugs.”

Worse still, in the case of treatment for infectious diseases with antibiotics or anti-malarials, some diseases can develop drug-resistance if the wrong dose of API has been administered.

To give an idea of the scale of the problem for human health, in 2008 the FDA recorded 81 deaths and about 600 allergic reactions resulting from a batch of counterfeit Herapin, a drug used to prevent blood clots.

“Counterfeit drugs raise significant public health concerns because their safety and effectiveness is unknown.” — Howard Sklamberg, deputy commissioner for global regulatory operations and policy, FDA

“Counterfeit drugs raise significant public health concerns because their safety and effectiveness is unknown,” said Howard Sklamberg, the FDA’s deputy commissioner for global regulatory operations and policy.

Supply Chain Problems

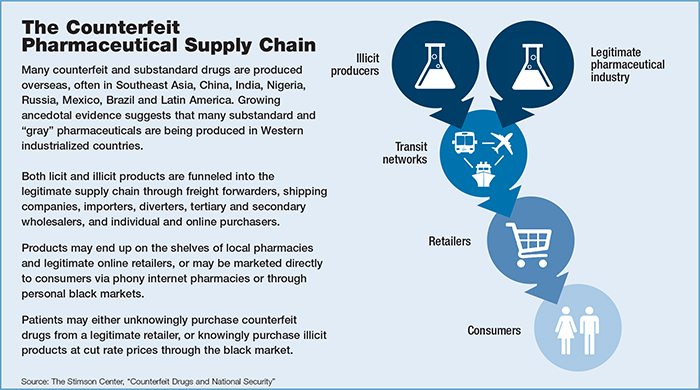

The problem of counterfeit drugs is made worse by an increasingly complex global supply chain network.

With almost 40 percent of all drugs that Americans take being made overseas, according to the FDA, the opportunity to infiltrate the supply chain with counterfeit drugs is far greater than before.

The fact that these drugs are imported also means they may have been mishandled, adulterated or counterfeited before entering the country.

“Patients expect the supply chain to work properly and if there’s a flaw in that chain it’s not only a potential risk to their own health, but also the reputation of the company making and selling that drug,” said Jim Walters, managing director of Aon Risk Solutions’ life sciences and chemical group.

Ned Milenkovich, principal and co-chair of the health care law practice at law firm Much Shelist, said that globalization was a key factor in the surge in counterfeit medicines.

“On the whole, the situation is worse internationally than in the U.S., where at least we have some safeguards to prevent these drugs entering the market,” he said.

Outside Influences

The majority of counterfeit drugs are manufactured outside the U.S., in largely unregulated markets such as China and India, according to the FDA.

Because of the relatively low production costs and the ease of transportation, as well as lighter penalties compared to other crimes like narcotics, they have become a magnet for international organized criminal gangs.

The markups are also far greater. For example, based on an investment of $1,000, the estimated profit from counterfeiting a blockbuster drug can be as high as $500,000 versus $20,000 for heroin.

“The criminal world has recognized the margins that can be made from counterfeit medicines and it is much easier to copy these kinds of drugs than it was five to 10 years ago,” said Aon’s Walters.

Counterfeiting is also closely linked to money laundering, drug trafficking and terrorism, said Robert Lane, global practice leader at Willis Resolutions and executive vice president at Willis Global Solutions.

“Terrorism is at the core of this,” he said. “There is a lot of money involved and because of advances in technology, criminals are able to create counterfeit products and maintain a relatively low profile in the process.”

Advances in Technology

Advancements in technology and the internet have also made it easier for criminals to sell their counterfeit drugs online, many of which are a fraction of the price of the original and are dispensed without prescriptions.

Many use sophisticated marketing techniques or fraudulent web storefronts to sell their wares, according to the FDA.

And because of increased technological sophistication, counterfeiters are often able to pass off fake medicines as the real thing, said Bassiur.

“The real danger in ordering these medicines over the internet is a complete lack of transparency and intentional deception, which is a big problem in developed nations where patients are increasingly turning to online to source their medicines,” he said. “However, there are places that people can safely buy prescription medicine online.”

Reputational Risk

While a patient’s health can be compromised by counterfeit drugs, manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies can suffer a huge financial loss in terms of sales.

Robert Lane, global practice leader, Willis Resolutions; executive vice president, Willis Global Solutions

It can also infringe on their patent and trademark rights, as well as damage their brand reputation as a result of the negative publicity.

“Essentially what is happening is that your drug is being hijacked,” said Lane.

“There’s infringement across the board in every context and the reputational and financial hit you take as a result can be substantial.”

A company stands to lose not only the benefit of its investment in research and development and advertising that drug, but also the expense of hiring outside experts to look into the problem, according to Dan Torpey, partner in EY’s fraud investigation and dispute services.

“Essentially, someone else is getting the benefit of all your work and effort off the back of sales of a counterfeit product,” he said. “Unfortunately, because a lot of these counterfeiters are rogue individuals or small groups there’s not much recourse for recovery other than enforcement.”

Laura Sunderlin, life sciences underwriter at Beazley, said that the bigger problem is for those companies in the supply chain who buy the drug without knowing it is counterfeit.

“The worst case would be a large distributor buying a big quantity of the drug and then it being passed on down the supply chain to the end consumer and the potential [repercussions] that could bring,” she said.

Tackling the Issue

The pharmaceutical industry has had some success in the fight against counterfeit drugs. In 2012, 79 arrests were made and $10.5 million worth of potentially lethal medicines was seized in Interpol’s Operation Pangea V, targeting illegal online pharmacies.

In November 2013, President Obama signed into law the Drug Supply Chain and Security Act. The act was designed to protect the public from exposure to counterfeit, stolen or otherwise harmful drugs by enabling the monitoring of certain prescription drugs as they move through the supply chain.

And in January 2016, the Council of Europe will bring into force the Medicrime Convention to police counterfeit drugs and prosecute offenders.

And in January 2016, the Council of Europe will bring into force the Medicrime Convention to police counterfeit drugs and prosecute offenders.

Many drugs companies have also implemented new technologies such as radio frequency identification (RFID) chips and tags to track and trace their products.

They also work with governments, regulators and bodies such as the IFPMA to combat the problem and to raise public awareness, as well as their own operations.

Sanofi, for example, has a dedicated team of experts who search for counterfeit drugs on the internet and has set up a central anti-counterfeit laboratory to analyze suspect products.

Walters, however, was a bit more skeptical about the problem. “While across the board there are lots of ways that companies are tackling the problem, conceivably there is no way that you are going to be able to monitor every single pill or capsule,” he said.

Available Coverage

Provided that there was no intent to defraud and they were unaware that they were buying and passing on counterfeit drugs in the first place, most companies in the supply chain will be covered by professional and product liability and errors and omissions insurance, said Sunderlin.

However, she said that the problem would continue until an international standard is brought in for monitoring all drugs.

“Until there is an international, required standard of protection for technologies used in legitimate drug packaging which would track a product from manufacturer to consumer, and would make it difficult and very expensive to try to counterfeit, there will be an increasing number of counterfeits introduced and sold around the world,” she said.

Bassiur added: “Counterfeiting is a multibillion dollar enterprise. Large profits, combined with little risk of meaningful penalties in many countries, fuel this illicit industry.

“At the end of the day, the counterfeiter doesn’t care about your health and safety or whether you live or die, they only care about getting your money and lining their own pockets.”