Aviation Woes

Coping with Cancellations

Airlines typically can offset revenue losses for cancellations due to bad weather either by saving on fuel and salary costs or rerouting passengers on other flights, but this year’s revenue losses from the worst winter storm season in years might be too much for traditional measures.

At least one broker said the time may be right for airlines to consider crafting custom insurance programs to account for such devastating seasons.

For a good part of the country, including many parts of the Southeast, snow and ice storms have wreaked havoc on flight cancellations, with a mid-February storm being the worst of all. On Feb. 13, a snowstorm from Virginia to Maine caused airlines to scrub 7,561 U.S. flights, more than the 7,400 cancelled flights due to Hurricane Sandy, according to MasFlight, industry data tracker based in Bethesda, Md.

Roughly 100,000 flights have been canceled since Dec. 1, MasFlight said.

Just United, alone, the world’s second-largest airline, reported that it had cancelled 22,500 flights in January and February, 2014, according to Bloomberg. The airline’s completed regional flights was 87.1 percent, which was “an extraordinarily low level,” and almost 9 percentage points below its mainline operations, it reported.

And another potentially heavy snowfall was forecast for last weekend, from California to New England.

The sheer amount of cancellations this winter are likely straining airlines’ bottom lines, said Katie Connell, a spokeswoman for Airlines for America, a trade group for major U.S. airline companies.

“The airline industry’s fixed costs are high, therefore the majority of operating costs will still be incurred by airlines, even for canceled flights,” Connell wrote in an email. “If a flight is canceled due to weather, the only significant cost that the airline avoids is fuel; otherwise, it must still pay ownership costs for aircraft and ground equipment, maintenance costs and overhead and most crew costs. Extended storms and other sources of irregular operations are clear reminders of the industry’s operational and financial vulnerability to factors outside its control.”

Bob Mann, an independent airline analyst and consultant who is principal of R.W. Mann & Co. Inc. in Port Washington, N.Y., said that two-thirds of costs — fuel and labor — are short-term variable costs, but that fixed charges are “unfortunately incurred.” Airlines just typically absorb those costs.

“I am not aware of any airline that has considered taking out business interruption insurance for weather-related disruptions; it is simply a part of the business,” Mann said.

Chuck Cederroth, managing director at Aon Risk Solutions’ aviation practice, said carriers would probably not want to insure airlines against cancellations because airlines have control over whether a flight will be canceled, particularly if they don’t want to risk being fined up to $27,500 for each passenger by the Federal Aviation Administration when passengers are stuck on a tarmac for hours.

“How could an insurance product work when the insured is the one who controls the trigger?” Cederroth asked. “I think it would be a product that insurance companies would probably have a hard time providing.”

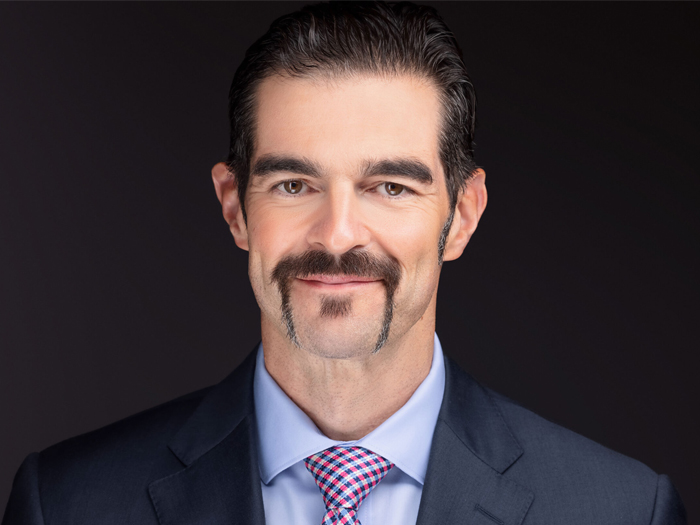

But Brad Meinhardt, U.S. aviation practice leader, for Arthur J. Gallagher & Co., said now may be the best time for airlines — and insurance carriers — to think about crafting a specialized insurance program to cover fluke years like this one.

“I would be stunned if this subject hasn’t made its way up into the C-suites of major and mid-sized airlines,” Meinhardt said. “When these events happen, people tend to look over their shoulder and ask if there is a solution for such events.”

Airlines often hedge losses from unknown variables such as varying fuel costs or interest rate fluctuations using derivatives, but those tools may not be enough for severe winters such as this year’s, he said. While products like business interruption insurance may not be used for airlines, they could look at weather-related insurance products that have very specific triggers.

For example, airlines could designate a period of time for such a “tough winter policy,” say from the period of November to March, in which they can manage cancellations due to 10 days of heavy snowfall, Meinhardt said. That amount could be designated their retention in such a policy, and anything in excess of the designated snowfall days could be a defined benefit that a carrier could pay if the policy is triggered. Possibly, the trigger would be inches of snowfall. “Custom solutions are the idea,” he said.

“Airlines are not likely buying any of these types of products now, but I think there’s probably some thinking along those lines right now as many might have to take losses as write-downs on their quarterly earnings and hope this doesn’t happen again,” he said. “There probably needs to be one airline making a trailblazing action on an insurance or derivative product — something that gets people talking about how to hedge against those losses in the future.”